- Very Rare Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures Study

- Very Rare Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures King James Version

- Very Rare Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures Verses

- Very Rare Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures Fulfilled

This clearly contradicts Scripture (e.g., Leviticus 17:11, Titus 3:5, Romans 4 and 5, etc.). Seventh, the apocryphal books were never accepted by the church until the Council of Trent. Roughly 1,500 years after these books were written, the Catholic church decided to “officially” recognize the apocrypha as Scripture.

Is the Apocrypha inspired scripture?

- It is very rare that any who are caught in this snare of the devil, recover themselves; so much is the heart hardened, and the mind blinded, by the deceitfulness of this sin. Many think that this caution, besides the literal sense, is to be understood as a caution against idolatry, and subjecting the soul to the body, by seeking any forbidden.

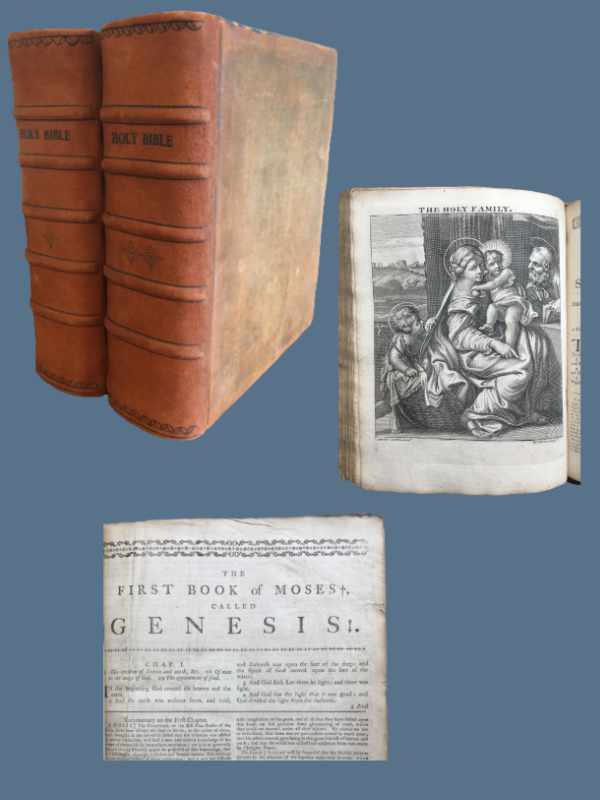

- VERY RARE and desirable. Our Guarantee: Very Fast. Free Shipping Worldwide. Customer satisfaction is our priority! Notify us with 7 days of receiving, and we will offer a full refund without reservation! Photos available upon request.

- Add Rare Bibles and Antiquarian Collectible Books to Your Manuscript Collection. Bibles have been printed in various editions for centuries, but many of them are rare and can be difficult for even seasoned collectors to locate. EBay lists a number of reasonably priced rare Bibles and antiquarian collectible books that you may wish to display or add to your library.

The term apocrypha has several meanings. From its Greek root, it means hidden, or concealed. However, it also referred to a book whose origin was unknown. Over time, this term came to be used to describe any book that was non-canonical. Today, due to the apocryphal books included in the Catholic Bible, most Protestants understand this term to refer to those books in the Catholic Bible that are not in the Protestant Bible.

Since the Catholic church believes it is infallible, and since they state that the Council of Trent issued infallible decrees, and since at the Council of Trent the Catholic church “infallibly” declared the apocryphal books to be canonical (i.e., God breathed Scripture), it is worth looking at these books and the reasons why the Jews and Protestants do not include them in their OT canon.

At Trent (Session IV), the Catholic church explicitly named the books of both the OT and NT: “It [the Council] has thought it proper, moreover, to insert in this decree a list of the sacred books, lest a doubt might arise in the mind of someone as to which are the books received by this council.” Going even further, the Council of Trent pronounced that those who do not accept the apocryphal books as Scripture are accursed:

“If anyone does not accept as sacred and canonical the aforesaid books in their entirety and with all their parts, as they have been accustomed to be read in the Catholic Church and as they are contained in the old Latin Vulgate Edition, and knowingly and deliberately rejects the aforesaid traditions, let him be anathema.”

If one believes the Catholic church is infallible, then it would be very important to follow their decree so as not to be anathematized (i.e., accursed). As we examine the apocryphal books, however, we’ll see that the Catholic church is not only not infallible, they are in gross error to include the apocryphal books.

Before we examine these books, it’s important to point out how we received the apocryphal books. The original OT canon was Jewish, and contained the twenty two books (the same thirty nine in today’s Protestant Bible). This canon was known as the Palestinian canon. When the Hebrew OT was translated into Greek (the Septuagint) in Alexandria, Egypt, included in the canon were fifteen books known as the Apocrypha. These were likely included due to the tradition of many churches viewing these books as “useful”, but not canonical, as we will see. It should also be noted that not all of these books were accepted by the Council of Trent. Per Vlach:

Very Rare Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures Study

“Of the fifteen books mentioned in the Alexandrian list, twelve were accepted and incorporated into the Roman Catholic Bible. Only 1 and 2 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh were not included. Though twelve of these works are included in the Catholic Douay Bible, only seven additional books are listed in the table of contents. The reason is that Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah were combined into one book; the additions of Esther were added to the book of Esther; the Prayer of Azariah was inserted between the Hebrew Daniel 3:23 and 24; Susanna was placed at the end of the book of Daniel (ch. 13); and Bel and the Dragon was attached to Daniel as chapter 14.”

Vlach also provides a very useful summary of each of these fifteen books, as shown below.

1. The First Book of Esdras (150—100 B.C.) (not included in Catholic Bible) – This work begins with a description of the Passover celebration under King Josiah and relates Jewish history down to the reading of the Law in the time of Ezra. It reproduces with little change 2 Chronicles 35:1—36:21, the book of Ezra and Nehemiah 7:73—8:13a. It also includes the story of three young men, in the court of Darius, who held a contest to determine the strongest thing in the world. 1 Esdras has legendary accounts which cannot be supported by Ezra, Nehemiah or 2 Chronicles.

2. The Second Book of Esdras (c. A.D. 100) (not included in Catholic Bible) Differs from the other fifteen books in that it is an apocalypse. It has seven revelations (3:1—14:48) in which the prophet is instructed by the angel Uriel concerning the great mysteries of the moral world. It reflects the Jewish despair following the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70.

3. Tobit (c. 200—150 B.C.) The Book of Tobit describes the doings of Tobit, a man from the tribe of Naphtali, who was exiled to Ninevah where he zealously continued to observe the Mosaic Law. This book is known for its sound moral teaching and promotion of Jewish piety. It is also known for its mysticism and promotion of astrology and the teaching of Zoroastrianism (The Bible Almanac, eds. Packer, Tenney and White, p. 501).

4. Judith (c. 150 B.C.) Judith is a fictitious story of a Jewish woman who delivers her people. It reflects the patriotic mood and religious devotion of the Jews after the Maccabean rebellion.

5. The Additions to the Book of Esther (140-130 B.C.) 107 verses added to the book of Esther that were lacking in the original Hebrew form of the book.

6. The Wisdom of Solomon (c. 30 B.C.) This work was composed in Greek by an Alexandrian Jew who impersonated King Solomon.

7. Ecclesiasticus, or the Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach (c. 180 B.C.) This book is the longest and one of the most highly esteemed of the apocryphal books. The author was a Jewish sage named Joshua (Jesus, in Greek) who taught young men at an academy in Jerusalem. Around 180 B.C. he turned his classroom lectures into two books. This work contains numerous maxims formulated in about 1,600 couplets and grouped according to topic (marriage, wealth, the law, etc.).

8. Baruch (c. 150-50 B.C.) This book claims to have been written in Babylon by a companion and recorder of Jeremiah (Jer. 32:12; 36:4). It is mostly a collection of sentences from Jeremiah, Daniel, Isaiah and Job. Most scholars are agreed that it is a composite work put together by two or more authors around the first century B.C.

9. The Letter of Jeremiah (c. 300-100 B.C.) This letter claims to be written by the prophet Jeremiah at the time of the deportation to Babylon. In it he warns the people about idolatry.

10. The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Young Men (2nd— 1st century B.C.) This section is introduced to Daniel in the Catholic Bible after Daniel 3:23 and supposedly gives more details of the fiery furnace incident.

11. Susanna (Daniel 13 in the Catholic Bible) (2nd — 1st century B.C.) In this account, Daniel comes to the rescue of the virtuous Susanna who was wrongly accused of adultery.

12. Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14 in the Catholic Bible) (c. 100 B.C.) Bel and the Dragon is made up of two stories. The first (vv. 1-22) tells of a great statue of Bel (the Babylonian god Marduk). Supposedly this statue of Bel would eat large quantities of food showing that he was a living god who deserved worship. Daniel, though, proved it was the priests of Bel who were eating the food. As a result, the king put the priests to death and allowed Daniel to destroy Bel and its temple. In the second story (vv. 23-42), Daniel, in defiance of the king, refuses to worship a great dragon. Daniel, instead, asks permission to slay the dragon without “sword or club” (v. 26). Given permission, Daniel feeds the dragon lumps of indigestible pitch, fat and hair so that the dragon bursts open (v. 27).

13. The Prayer of Manasseh (2nd or 1st century B.C.) (Not in Catholic Bible) This work is a short penitential psalm written by someone who read in 2 Chronicles 33:11-19 that Manasseh, the wicked king of Judah, composed a prayer asking God’s forgiveness for his many sins.

14. The First Book of the Maccabees (c. 110 B.C.) “The First Book of Maccabees is a generally reliable historical account of the fortunes of Jewish people between 175 and 134 B.C., relating particularly to their struggle with Antiochus IV Epiphanes and his successors. . . . The name of the author, a patriotic Jew at Jerusalem is unknown” (Metzger, p. 169). The book derives its name from Maccabeus, the surname of a Jew who led the Jews in revolt against Syrian oppression.

15. The Second Book of the Maccabees (c. 110-70 B.C.) This book is not a continuation of 1 Maccabees but an independent work partially covering the period of 175-161 B.C. This book is not as historically reliable as 1 Maccabees.

Why Christians Reject the Apocrypha

Why do Christians reject the Apocryphal books as canonical? There are at least eight good reasons why Christians reject the apocryphal books as being included in the OT canon. These include history and evidence from some of the books themselves.

First, no apocryphal books were written by a prophet. All of the OT Scriptures were written by prophets, while none of the apocryphal books were; therefore, the apocryphal books are not canonical. Scripture attests to this view in that the OT is referred to as the Scriptures of the prophets. Specific references include (with emphases added):

So we have the prophetic word made more sure, to which you do well to pay attention as to a lamp shining in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star arises in your hearts. (2 Peter 1:19)

But now is manifested, and by the Scriptures of the prophets, according to the commandment of the eternal God, has been made known to all the nations, leading to obedience of faith; (Romans 16:26)

As He spoke by the mouth of His holy prophets from of old. (Luke 1:70)

But Abraham said, 'They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them.” (Luke

16:29)

Then beginning with Moses and with all the prophets, He explained to them the

things concerning Himself in all the Scriptures.” (Luke 24:27)

God, after He spoke long ago to the fathers in the prophets in many portions and in

many ways (Hebrews 1:1)

More Scripture could be quoted, but clearly, the prophets are equivalent to the OT, as God spoke His word solely through prophets. Furthermore, it is generally agreed (especially among the Jews) that Malachi was the last prophet before John the Baptist. Yet most of the writers of the apocrypha lived after Malachi. In addition, the apocrypha was not written in Hebrew as was all of the OT (most were written in Greek). If inspired, it would only make sense that the writers would write in the language of Israel.

Second, the apocryphal books were not accepted by the Jews as part of the OT. If these books were part of the canonical OT, then surely Jesus would have criticized the Jews for excluding them from Scripture, yet He never does.

Third, Jesus and the apostles never quote from the apocryphal books. The OT testifies of Christ, and He gives testimony to the validity of the OT by quoting from many of its books. The apostles, likewise, quote from the OT. Yet they never quote from any of the apocryphal books.

Why does Jude quote the Book of Enoch then? This book was not one of the apocryphal books of which we’re speaking; rather, it was part of the Pseudepigrapha, which were a set of supposed scripture that were universally rejected as false writing. Nevertheless, Jude mentions the book because it was well known in his day, and evidently it contained some useful information despite not begin inspired scripture.

Just because Jude quotes this book does not mean Enoch is inspired. If that logic were true, then we’d have to say that heathen writings are also inspired. This is because Paul quotes from certain heathen poets, such as Aratus (Acts 17:28), Menander (1 Corinthians 15:33), and Epimenides (Titus 1:12). Just because Scripture quotes a truthful source does not make that source automatically inspired Scripture.

Fourth, many Jewish scholars and early church fathers rejected the apocryphal books as canonical. Jewish writers such as Philo and Josephus, and the rabbis at the Council of Jamnia all rejected the apocryphal books as canonical. Most of the early church also rejected them, including Origen, Athanasius, Hilary, Cyril, Epiphanius, Ruffinus, and Jerome. Interestingly, cardinal Cajetan, the man the Catholic church sent to debate Luther, also rejected these books as canonical. In his commentary of the history of the OT, he writes the following:

“Here we close our commentaries on the historical books of the old Testament. For the rest (that is, Judith, Tobit, and the books of Maccabees) are counted by St Jerome out of the canonical books, and are placed amongst the Apocrypha, along with Wisdom and Ecclesiasticus, as is plain from the Prologus Galeatus. Nor be thou disturbed, like a raw scholar, if thou shouldest find any where, either in the sacred councils or the sacred doctors, these books reckoned as canonical. For the words as well of councils as of doctors are to be reduced to the correction of Jerome. Now, according to his judgment, in the epistle to the bishops Chromatius and Heliodorus, these books (and any other like books in the canon of the bible) are not canonical, that is, not in the nature of a rule for confirming matters of faith. Yet, they may be called canonical, that is, in the nature of a rule for the edification of the faithful, as being received and authorized in the canon of the bible for that purpose. By the help of this distinction thou mayest see thy way clearly through that which Augustine says, and what is written in the provincial council of Carthage.”

This is interesting because not only is cardinal Cajetan a Catholic, he also provides evidence for how some viewed the apocryphal books as canonical, the most famous of which is Augustine. There is other evidence from Augustine that corroborate this view, meaning when he said the apocrypha was canonical, he did not mean it in the sense of being inspired. Rather, it was meant in the sense of being useful for edification.

Indeed, Athanasius, after naming the twenty two Hebrew OT books (thirty nine in Protestant Bibles), says “But, besides these, there are also other non-canonical books of the old Testament, which are only read to the catechumens.”, and then he names the apocryphal books. This is why Jerome included those books in the Latin Vulgate, which he translated.

Fifth, some apocryphal books contain many historical and geographical inaccuracies. As we have shown in our prior study on the inspiration of Scripture, the Bible does not contain such inaccuracies. These errors prove the books that contain them are non- canonical. Some of the errors are shown below:

- There are several inconsistencies in the additions to Esther, one of which in chapter 6 mentions Ptolemy and Cleopatra. Both lived after the times of Mordecai, so including these two later historical figures clearly shows this addition was written well after Esther was completed. In addition, the added chapters were written in Greek, not Hebrew.

- In the book of Judith, Holofernes is incorrectly described as the general of “Nebuchadnezzar who ruled over the Assyrians in the great city of Ninevah” (1:1). In truth, Holofernes was a Persian general, and Nebuchadnezzar was king of Babylon.

Sixth, the apocryphal books often contradict Scripture. Examples include:

- The Book of Tobit teaches magic (Tobit 6:4,6-8). The Bible clearly condemns magical practices such as this (consider Deuteronomy 18:10-12; Leviticus 19:26,31; Jeremiah 27:9; Malachi 3:5).

- 2 Maccabees 12:43-45 states: “He also took up a collection ... and sent it to Jerusalem to provide for a sin offering. ... For if he were not expecting that those who had fallen asleep would arise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead ... Therefore he made atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sin.” This teaches prayers for the dead, as well as salvation by works, both of which contradict Scripture. Hebrews 9:27 makes clear that judgment comes after death, while numerous Scriptures clearly show that salvation is solely by faith in Christ alone.

- The Book of Tobit 12:9 states: “For almsgiving delivers from death, and it will purge away every sin.” This clearly contradicts Scripture (e.g., Leviticus 17:11, Titus 3:5, Romans 4 and 5, etc.).

Seventh, the apocryphal books were never accepted by the church until the Council of Trent. Roughly 1,500 years after these books were written, the Catholic church decided to “officially” recognize the apocrypha as Scripture. As we’ve seen above, these books were not accepted as canonical Scripture by either the Jews or the early Christian church. It is clear that the Catholic church adopted these books as canonical in opposition to Protestantism, as some of the apocrypha (falsely) supported Catholicism’s teaching regarding salvation.

And finally, no apocryphal book makes the claim that it is the word of God. While most OT books do claim to be God’s word, none of the apocrypha claim this status.

While some of the apocryphal books are useful, especially from a historical perspective, it’s clear they are not inspired, and therefore do not belong in the OT canon. We encourage believers to read these books, however, so they can judge for themselves as well.

You may also be interested in another article on why we can trust the BIble.

do you have a question you need an answer to?

Bible answers

Submit a Question

Related Questions

QHow were the 66 books of the Bible selected?

06.04.2014

QAre Roman Catholics truly Christian?

11.02.2015

QWhen is the Catholic pope’s proclamations considered “infallible”?

09.14.2013

by Ron Davis (expanded from the Bible Review Journal - Fall 2014)In the seventeenth century, the Geneva Bible, brought to Plymouth in 1620, and likely to Jamestown in 1607, was gradually replaced by the King James Bible in the American colonies. In the eighteenth century, Pennsylvania surpassed Massachusetts in the printing of the Scriptures. In the nineteenth century, the hub shifted from Pennsylvania to New York, where the American Bible Society was located. Innovations and technological advances allowed the printing and distribution of large quantities and a diverse array of Scriptures by the mid-nineteenth century. The Bibles, New Testaments, and Bible portions met the spiritual needs of America’s growing and ethnically changing population.

Massachusetts Puritans

The Bible of the Pilgrims, who landed at Plymouth in 1620, was the Bible first published in Geneva in 1560. Protestant Reformers John Calvin, Theodore Beza, and John Knox were active in Geneva, a primarily French-speaking Protestant republic. The Geneva Bible was a scholarly revision of the Great Bible (Cranmer Bible). No translators are specified, but the New Testament is generally credited to William Whittingham, brother-in-law of John Calvin. Whittingham was helped by Anthony Gilby, Thomas Sampson, William Cole, Christopher Goodman, and Laurence Thomson, especially in completing the Old Testament. These Englishmen were in Switzerland because of persecution during the reign of Mary Tudor in England, and came to be known as Marian exiles. John Calvin, Theodore Beza, John Knox, and Miles Coverdale helped in translating and editing work, and Calvin wrote the introduction. The Geneva Bible had marginal notes containing Calvinist theology. It is nicknamed the Breeches Bible because of its quaint rendering of Genesis 3:7, “They sewed fig tree leaves together and made themselves breeches.” The Bible was a result of several years of diligent labor. Whittingham had previously produced a New Testament (1557), which was William Tyndale’s 1534 New Testament with changes from the Great Bible.

The Geneva Bible had features, novel for its time, which made it popular. It went through as many as two hundred editions in the hundred years following its 1560 first printing in Geneva. In England the first printing was in 1575 by Christopher Barker. English-language Geneva Bibles were later published in Holland, especially after 1616. The Geneva Bible was the first Bible in the English language to contain verse divisions for easy reference. It used smaller Roman type, rather than the customary, heavy black-letter, Old-English type. The Geneva Bible italicized English words not found in the original Hebrew and Greek. It was mostly printed in a convenient quarto or octavo format, less expensive and ponderous than earlier folio English versions. It also contained prefaces, marginal notes, annotations, and popular illustrations and maps, which helped clarify the text. The Geneva Bible was the Bible of such famous Englishmen as William Shakespeare, Oliver Cromwell, John Milton, and John Bunyan. Bible quotations in Governor William Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation were from the Geneva Bible, as were those of William Strachey, the secretary of the Virginia Company, in his history of Virginia (1609-1612). The earliest published sermons and writings in New England are evidence of almost exclusive use of the Geneva version. In Virginia, sermons of a prominent minister William Whitaker, were from the Geneva Bible.

The King James Bible, or Authorized Bible as it was called in England, although first published in 1611, did not supersede the Geneva Bible in the American colonies until the 1640's. It was, however, in widespread use earlier in Virginia and the middle colonies than in New England. The unequaled quality and literary beauty of the King James Version made it, by 1690, the overwhelming Bible of choice in the English-speaking world.

In 1640, Stephen Daye of Cambridge, Massachusetts, printed the first book in America, still extant, the New England version of the Psalms, commonly called the Bay Psalm Book (Evans 4). It was compiled and prefaced by Richard Mather (1596-1669), minister of the church of Dorcester, and co-authored with Thomas Weld and John Eliot, the first and second ministers at Roxbury respectively, and John Cotton, a minister in Boston. Daye printed 1600 copies of the 1640 first edition at a total cost of 33 pounds, the books being priced at 20 pence each. There are today about a dozen copies of the first edition extant. The Bay Psalm Book though frequently reprinted is scarce. When Colonial editions come to auction they command among the highest prices of books printed in America. The 1698 ninth edition of the New England psalter contains pages of woodcut music to facilitate church singing.

The most famous and valuable early American Bible is a translation into the Massachuset (Natick) dialect of Algonquian by Massachusetts Congregational minister and missionary, John Eliot (1604-1690), published in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Eliot graduated from Cambridge University in England and came to America in 1631. He produced a Primer or Catechism in Algonquian (1654), and translated and secured publication of Genesis (1655), Matthew's Gospel (1655), and the Psalms (1658). A New Testament was published in 1661 (Evans 64), and the whole Bible in 1663 (Evans 72). The printers were Marmaduke Johnson (sent over from England) and Samuel Green, with help from a Nipmuc Indian, James Wawaus (aptly given the name James Printer), who labored as a compositor and corrector of the press. The New Testament was printed again in 1663 and 1680 with the title in the Massachuset dialect instead of English. The Bibles are small quarto format. Peter S. Du Ponceau did an annotated edition of the 1663 Eliot Bible in Boston in 1822.

After the Christian Indian losses as a result of the disastrous King Philip’s War (1675-1676), a second edition of the Eliot Bible was published (1685), printed by Samuel Green of Cambridge. Some Eliot Bibles and New Testaments, in collections today, contain the signatures of their previous Indian owners and show evidence of heavy use. Mashpee Indians, who had the highest literacy rate among the Massachuset Indians, still owned copies of the Eliot Bibles in the nineteenth century. Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island, a friend of the Indians and author of A Key into the Language of America, owned a copy in which his handwritten marginal notes are preserved.

John Eliot saw between 2,500 and 4,000 Native Americans turn to Christ in thirty years of mission work. Fourteen “Praying Indian” communities were established, beginning with the town of Natick, but the King Philip’s War was a severe setback. Only four of the original towns survived the war. Eliot, although discouraged, persevered in the work until his death at the age of 85. He vowed, “I can do little, yet I am resolved through the grace of Christ, I will never give over the work, so long as I have legs to go.”

Robert Boyle (1627-1691), famous Irish-born chemist, physicist, and formulator of Boyle’s law of gases, was a major contributor to Eliot’s Bible from England. Because substantial financial support for publication came from England, and because the “Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England” had been organized in England to support the mission work in Massachusetts, some of these first Bibles were sent back to England. Forty copies of the 1661 Eliot first edition were sent to London to the Governor of the Commissioners of the New England colonies, later ending up in public institutions in England. Darlow and Moule summarize the historic significance of the Eliot Bibles, “They constitute the earliest example in history of the translation and printing of the entire Bible in a new language as a means of evangelization.”

In 1709 The Massachuset Psalter: or, Psalms of David With the Gospel According to John in Columns of Indian and English was produced by Experience Mayhew, for use by the indigenous people of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket. Mayhew was a resident of Martha's Vineyard. The text was printed by B. Green and J. Printer in Boston with the Massachuset and the English in collateral columns. The project was supported by the “Honourable Company for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England.”

A prayer book with Scripture selections from the first three chapters of Genesis, parts of the first five chapters of Matthew, as well as some detached sentences from the remainder of the New Testament was published in 1715 in Mohawk by William Bradford in New York. The translation was done by Lawrence Claesse, interpreter to missionary William Andrews. Rev. Cotton Mather anonymously produced a translation of some Scriptures in blank verse, the Psalterium Americanum which in 1718 was printed in octavo by S. Kneeland in Boston.

Pennsylvania Germans

The first Bible published in America in a Modern or European language was by Christoph (Christopher) Saur (1695-1758), who was born near Heidelberg in the Palatine, the son of a Reformed pastor. He immigrated from Wittgenstein in central Germany to Germantown (by Philadelphia) in 1724. Saur maintained ties with Radical Pietist and Inspirationist communities in Germany, and with the Anabaptist Brethren (Dunker, Dunkard, Tunker) communities in Pennsylvania, though there is no record of his actually becoming a member of the Brethren Church. His wife, Maria Christina, joined the Ephrata Cloister in 1730, becoming Sister Marcella, prioress and later sub-prioress, until returning to her husband in Germantown in 1744. Saur learned printing skills from the Ephrata brethren, some of whom had previously learned the skills in their European homeland. Saur also received his first contractual printing job (an Ephrata Cloister hymnal) from Ephrata.

Saur’s German-language Bible was published in an edition of 1200 copies in Germantown in 1743 (Evans 5128, D & M 4240, Arndt 47, Hildeburn 804) after fifteen months of labor, assisted by Johannes Hildebrand, Jacob Gast, and possibly Peter Miller and Samuel Eckerling, all experienced printers of Ephrata. It was the 34th Halle edition of Martin Luther’s version. The one-volume Halle version was designed by the Lutheran Pietist August Franke to be affordable. However, Saur made revisions to it using the Berleburg Bible, which was published in Berleburg, Germany, in 8 volumes between 1726 and 1742 by Radical Pietists of Saur’s homeland. Saur published his one-volume German Bible in a large quarto, which was customarily bound in heavy, beveled boards covered with leather and secured with two brass clasps. Unbound Bibles cost twelve shillings (equivalent to about $80 today), while copies bound at the shop of the Ephrata brotherhood cost eighteen shillings (about $120). The paper for the Bible was traditionally thought to have been imported from Europe, but some experts believe the paper came from the Rittenhouse mill in Philadelphia or the Cloister mill in Ephrata. Seidensticker wrote in the preface to his 1893 book, “Quite notable among German publications are the Germantown editions of the Bible, respectively of 1743, 1763, and 1776 all quarto size and well printed on good Rittenhouse paper.” A different view is given by Eugene Doll who writes that “the Cloister paper mill furnished some of the paper for this great undertaking.” Lawrence Wroth, in The Colonial Printer, also writes that the paper for the Bible may have come from Ephrata. E. G. Alderfer, writing about the 1743 Bible, concurs: “For the most part the excellent paper it was printed on was manufactured in Ephrata’s new paper mill.” Another expert, Dard Hunter, in a letter to Rumball-Petre, wrote “the paper was made in this country and “the paper is too poor for English manufacture.” There were about seven paper mills in America at the time, most of these, including Rittenhouse and Ephrata, being in Pennsylvania. Possibly, both imported and Pennsylvania paper was needed to print the 1200 large, quarto-sized Bibles (with Apocrypha), each of which were at least 1267 pages in length. Some of the Bibles also contained, as an option, three other books from the Berleburg Bible, the third and fourth book of Ezra and the third book of Maccabees. Saur printed the Bibles for fellow German refugees in Pennsylvania, and claimed that “for the poor we have no price.” Yet the 1743 Bibles did not sell out for twenty years, five years after Saur’s death. Saur also published German New Testaments in 1745 (Evans 5542) and 1755 (Evans 7359).

Christoph Saur shipped a dozen copies of his 1743 German Bible to Dr. Heinrich Luther in Frankfurt, since Dr. Luther had sent the metal type to Saur for printing the Bibles. The ship was held up by pirates but, miraculously, the Bibles reached Dr. Luther two years later. These Bibles are in public institutions in Germany today. In 1940 Edwin Rumball-Petre, in America’s First Bibles, registered 134 copies of the 1743 Bible in America, Germany, Denmark, and England.

Christoph Saur Jr. (1721-1784) arrived with his father in America in 1724. He published the second Saur Bible in 1763 (Evans 9343) in an edition of 2000 copies. It has been dubbed the first Bible printed in America on American-made paper, even though American paper was probably used for the 1743 Bible. Rumball-Petre located only 125 copies of the 1763 edition in public and private collections worldwide. The younger Saur printed German New Testaments in 1760, 1761, 1763, 1764, 1769, and 1775. By 1773 he had built a paper mill to ensure adequate paper supplies for his printing business, and had become one of the wealthiest men in America. Presumably, then, Saur's 1775 New Testament (Evans 13837) and 1776 Bible used paper from his own mill.

In 1776, Christoph Saur Jr. reprinted the German Bible in an edition of 3000 copies (Evans 1463). It is thought to be the first American Bible made with American type rather than imported type. It has also been nicknamed the “Gun Wad Bible,” because according to legendary accounts, the Bible pages were supposedly used by either English or American soldiers to make gun wads for their rifles and for firewood and horse bedding. In a sad footnote to American history, Christoph Saur Jr. was accused in 1777, apparently falsely, of being disloyal to the colonies. He was arrested, and his property, including the printing press, was eventually confiscated and auctioned. Christoph Saur Jr., a Brethren elder, was a pacifist but not a Loyalist. Two of his sons, Christoph Saur III and Peter Saur, however, were Loyalists, and migrated to Canada and the West Indies, respectively, after the war.

Legend has it that much of the 1776 edition did not survive; yet in 1940 Rumball-Petre registered 195 copies, more copies than for either the 1743 or 1763 editions. Altogether, he registered 454 copies of the three editions. Today, the 1743 Saur Bible is the scarcest of the three, further evidence that the “Gun Wad” story is merely a legend.

The Saurs, father and son, also published Psalters (hymnals) for use in singing. A third-generation Saur, Samuel Saur (1767-1820), the youngest son of Christoph Saur Jr., published Psalters in 1791, 1796, and 1797. He moved from Germantown to Baltimore in 1794, and the 1796 Psalter has been cited as the first portion of Scripture published in the American South. Samuel Sower, as documented in Isaiah Thomas’ book on early American printing, developed a type making business in Baltimore, S. Sower and Company. Samuel Saur cast an undersized Diamond type for a small (5 inch height) English-language Bible, the “First American Diamond Edition.” The Bible was printed by his nephew Brook W. Sower (son of Christoph Sower III) in Baltimore in 1812 (Hills 217), probably the first Bible printed in Maryland. This pocket-sized Bible without Apocrypha contained, after the title page, a seven-page Synopsis or “Brief Commentary” for each of the 66 books of the Bible. Pocket-sized New Testaments (5 inch height) had previously been printed in English by Brook Sower in Baltimore (1810, 1811), the 1810 edition being the first Maryland New Testament (Hills 185). Variations on the Saur name are Sauer and Sower; English-language books generally use the spelling Sower. Christopher Sower Company of Philadelphia published education books into the twentieth century.

German New Testaments (Martin Luther versions) were published in Philadelphia by Melchior Steiner in 1783 (Evans 17846) and Carl (Charles) Cist in 1791 (Evans 23202) and 1796 (Evans 30082). Steiner and Cist had been partners in a printing business from 1776 to 1781. The Russian-born Cist, a Moravian, later published a New Testament in English in 1799 (Hills 70). Carl Cist, whose birth name was Carl Thiel, was apparently the first in America to publish New Testaments in more than one language, and was also the first in America to publish a pharmacopoeia. Cist also printed, in English, the second volume of the three-volume 1791 Wesley New Testament (Hills 35).

In 1787, German New Testaments were printed in Pennsylvania by Sabbatarian (Seventh Day) Dunkers of the Ephrata Cloister and by a Lutheran printer, Michael Billmeyer. Each had Saur connections.

German Seventh Day Baptists led by Johann Conrad Beissel (1691-1768) had established the Ephrata Cloister, a semi-monastic community on the banks of Cocalico Creek, where the first building was erected in 1733. Beissel had come to America in 1720, and had been apprenticed in Germantown to Peter Becker, who baptized him in 1724. In 1728 Beissel had the first German-language book in America, his book about the Sabbath, Da Buchlein vom Sabbath, published by Andrew Bradford. Christopher Saur had been with Beissel in Ephrata before either man had established a printing business. Saur in his first year of printing had begun work on a monumental 800-page hymnal for the Cloister, Zionitischer Weyrauchs-Hugel (Hill of Zionitic Incense) which was published in 1739, the first book printed in German Fraktur typeface in America. Ephrata Cloister’s own publishing business began soon after Saur’s, and Doll and Funke’s Ephrata bibliography, lists 88 titles produced by Ephrata between 1745 and 1800, mostly in the German language. Pennsylvania historian John Bradley updates this to “more than 125 publications.” Alderfer writes that the Ephrata Cloister could, by the mid-1740s “claim the only complete printing, binding, and publishing establishment in America.” Ephrata printed hymnals, devotional books like The Pilgrim’s Progress (1754), and New Testaments. TheCloisters translated from the Dutch into German, and printed for the Mennonites, the Blutige-Schauplatz (The Bloody Theater orMartyrs’Mirror) in 1749, the largest book (1512 pages) printed in Colonial America.

Christoph Saur and Conrad Beissel were the most influential printers in Colonial America, as well as the earliest German-language printers in Pennsylvania, other than Philadelphia printers Benjamin Franklin and Andrew Bradford. Franklin and Andrews had printed in German, between 1728 and 1738, about ten books, an almanac, and a short-lived newspaper, using unpopular Latin (antigua) typefaces. Fraktur (Gothic, block) type was first used in America by Christoph Saur in 1738, having been imported from a foundry in Frankfurt. Fraktur typeface was easier to read than antigua for the German settlers, already accustomed to Fraktur in their homelands.

The Ephrata New Testaments are now scarce; remarkably, none are listed in O’Callaghan’s nineteenth-century reference book. The Ephrata imprints are described in books by Oswald Seidensticker (1889) and John Wright (1894). Ephrata published New Testaments in 1787, 1795, and 1796, and Psalters in 1793, 1795, and 1797. The Testaments were of different versions, Froschauer’s and Luther’s. The Bibles have 16-17 cm. cover height, and have been traditionally labeled duodecimos, but libraries now often list these, and other old duodecimo books, as octavos.

The Ephrata 1787 edition (Evans 20235), Das Ganz Neue Testament unsers herrn Jesus Christi, notes Seidensticker, is “not Luther’s translation, but one originally made in Switzerland.” Wright’s Early Bibles of America (3rd ed., 1894) pictures the 1787 Ephrata Testament title page, and elaborates on the book: “It is printed in bold, clear-faced type, and is a most admirable example of early book-making. It is greatly prized by collectors, and brings a high price.” A note at the end of the New Testament notes that this version was “Formerly printed at Zurich, Basle, as well as Frankfort and Leipsic: now however, at Ephrata, at the expense of the Brethren, in the year 1787.” The 1787 Testament was in Julius Sachse’s collection of Ephrata Cloister materials, and was also described by him: “The First American Edition of the celebrated Froschauer Testament. Excessively rare, and not in O'Callaghan. The Ephrata community rarely printed a book without some hymns, and the Testament was no exception.” Four hymns are printed at the end of the 1787 Testament. The Ephrata Testament was a reprint from the Swiss-German Bible, Christoph Froschauer’s 1529 “combined” version, and more specifically, the Taufer Testament, published in Zurich two hundred years later (in 1729) from the Froschauer text. The 1787 Ephrata edition was done for the Pennsylvania Mennonites by the Cloister. This New Testament is today in the collection of the University of Bern (Switzerland), the Mennonite Historical Library (Goshen, Indiana) and several Mennonite colleges, the Pennsylvania State Library (Harrisburg), the Free Library (Philadelphia), and the Beegley Library (Juniata College, Huntingdon, PA). Juniata, a Brethren college, also has one of the old Ephrata Cloister Presses and the recently-acquired Snow Hill (a branch of Ephrata Cloister) book collection. I located copies of this 1787 version in just over a dozen library collections in the United States. More than half the copies are located are in Pennsylvania, the Free Library and the Pennsylvania State Library having multiple copies. Several copies are also in public collections in Europe. The 1787 Ephrata Testament is the first Swiss version, and also the first version with hymns, printed in America.

The 1795 and 1796 (30081) Ephrata New Testaments and 1797 Psalter are Martin Luther versions and give Benjamin Mayer (variant spelling Meyer) as the printer. Benjamin Mayer moved on to print the Luther version of the German New Testament again in Harrisburg in 1800 (Evans 36956). The 1795 Ephrata “Psalterspiel” (hymnal) credits “der Neuen Buchbruderen” and Solomon Mayer; Das Kleine Davidische Psalterspiel der Kinder Zions, is the same Anabaptist version as Samuel Saur’s 1791 and 1797 hymnals. Seidensticker writes of this German hymnal, “The American reprint became popular with some Sects, Dunkers, Mennonites, etc., as evidenced by the numerous editions of the book: 1744, 1760, 1764, 1777, 1778, 1781, 1791, 1795, 1797, 1813, 1829.”

Michael Billmeyer (1752-1837), a Lutheran, along with his father-in-law, Peter Leibert, a Brethren minister, acquired in 1783 what was usable of the Saur printing equipment, and established a printing business in Germantown. After about three years, Leibert started a new printing business, and Billmeyer became sole proprietor. Billmeyer was a prolific printer of the German New Testament (Das Neue Testament) in the Martin Luther version, beginning with the 1787 first edition (Evans 20236). The Billmeyer New Testament was popular and was reprinted in 1788 (Evans 20969), 1795, 1803, 1807, 1808, 1810, 1819, and 1822. These have traditionally been listed as duodecimo (12mo) format and are about 17 cm in height. They are bound in leather secured with two brass clasps on leather straps attached to the back cover.

Today the Billmeyer New Testaments, particularly the editions of the early nineteenth century, are easier to find than the Saur and Ephrata Scriptures, and often have intact clasps. Billmeyer also frequently printed Psalters or hymnals. One he printed, Der Psalter des Konigsand Propheten Davids verdeutschet von D. Martin Luther was used widely by Lutheran churches, but also by others. This Psalter, for example, was also the one published in 1793 and 1797 at Ephrata. The Billmeyer Testaments and Psalters are in many public library collections.

Gottlob Jungmann printed a large German Bible (1805), the first German Lutheran quarto Bible printed in America and the first Bible of Reading, Pennsylvania. The Bible contains Jungmann's preface and quotes most of the preface of Christoph Saur Jr. as found in the 1776 Bible. The Jungmann Bible looks similar to the Saur Bible and was referred to as “in substance a second Saur” by Wright.

In 1813, Friedrich (Frederick) Goeb, in Somerset, Pennsylvania, then a village of 75 dwellings and 150 people, printed the first Bible west of the Allegheny Mountains (the first Bible of western Pennsylvania). It was a large German Lutheran quarto (Shaw & Shoemaker 30871), crafted with leather over oak boards. Some writers refer to it as a folio since it is almost 13 inches in height. Goeb, a Lutheran, worked in a cabin from 1810 to 1813 to produce the Bible, while at the same time rearing a large family with his wife Catherine. It has been estimated that as many as 5 million type settings (including blank spaces) were needed to complete the Bible. The master printer followed up in 1814 with a German New Testament. In 2013 Somerset celebrated the bicentennial of the Goeb Bible. By comparison, the much larger city of Pittsburgh, further west, did not produce a New Testament until 1815 (Hills 285) and a Bible until 1818 (Hills 349). The English-language Pittsburgh Bible, a small octavo, was published by Cramer and Spear using the spelling “Pittsburg” on the title page. This Pittsburgh Bible (Hills 349) has the distinction of being the first Bible printed west of the Allegheny River (which is farther west than the Allegheny Mountains). The Pittsburgh Bible was not listed by O’Callaghan in the nineteenth century and, according to Rumball-Petre, is today a very scarce Bible.

In 1819, Johann Bar in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, printed a massive German folio Bible, a Bible larger than any Bible previously printed in America. The Apocrypha is in smaller print than the rest of the Bible text. The Johann Bar Bible is substantial in both printing and binding, and contains frontispiece engravings to the Old Testament (Moses with the Tables of the Law) and the New Testament (Adoration of the Shepherds) by the engraver J. Henry.

First Bibles in English

The Aitken Bible, a King James Version, was the first English-language Bible published in America. This was at the close of the Revolutionary War. During most of the War for Independence (1775-1783), Bibles from England were unobtainable, and Congress seriously considered importing them from Holland and Scotland. In the Colonial era, England had banned the printing of the English Bible in America in order to give a monopoly to the three British publishers licensed by the Crown. Robert Aitken (1734-1802), a Scottish immigrant and Quaker, had been one of the five printers who had made bids to Congress to print Bibles. Aitken had already published the Congressional Quarterly and owned the largest bookstore in Philadelphia. His publication of the first New Testament in English in 1777 (Hills 1) was a financial success, and he followed up with reprints of the Testament in 1778, 1779, and 1781. In 1782 Aitken published 10,000 copies of the whole Bible (Hills 11), a small duodecimo (just over 5 by 3 inches in size) without pagination and with almost no margins. The Bible succeeded in being the only Bible ever authorized by Congress, but ruined him financially. He had published the nearly 2000-page Bible in a relatively large edition for the times. The Revolutionary War ended, and better-quality, imported Bibles became available. Aitken never again published Bibles.

In 1940, Rumball-Petre registered 71 copies of the Aitken Bible and estimated that there were less than 100 extant. These are in either one volume or two, and typically in poor condition. Aitken sent a presentation copy of the 1782 Bible to Oliver Hazard in London, England, “the first copy of the first edition,” two volumes in “olive green leather.” It can now be seen at the British Museum. Another, near-perfect, copy in original binding can be seen at the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England, an important repository of old Bibles and canonical manuscripts.

In 1790, Mathew Carey (1760-1839), an Irish journalist and immigrant, produced, in two volumes, the first Catholic Bible (and first English quarto Bible) of America (image). This was from the 1763-1764 second Challoner edition of the Douay-Rheims version (variant spellings: Douai, Doway, Rheems, Rhemes). This Bible (Hills 23) was printed in smaller numbers (about 470 copies) than other early American Bibles, because there were far fewer Catholics than Protestants in early America. John Carroll, the American Catholic superior who had encouraged Carey, estimated a Catholic population of only 25,000, out of 3.5 million total inhabitants in America in 1785. The Carey Catholic Bible is apparently rarer than either the Eliot Bible or the Aitken Bible. In 1954 only 35 copies of the Carey Catholic Bible were extant.

Carey did not publish another Bible for over ten years, but in the first two decades of the nineteenth century he became one of the biggest booksellers, and the most prolific publisher in America of the King James Bible. In 1805 Carey also printed another Douay-Rheims translation of the Latin Vulgate (Hills 120) (image), this time a reprint of Dr. Troy's 1791 Dublin edition. Rheims New Testaments from the Vulgate were also published by Carey in 1805 (Hills 126) (image), 1811 (Hills 196), and 1816 (Hills 309), the last a school edition containing the Psalms. Carey become one of the most prominent and respected printers in America. In 1801 he was the first president of a company organized in New York that represented American booksellers around the country.

It should be noted that Saur, Aitken, and Carey, the first three printers of modern-language Bibles in America, were from Philadelphia. In 1790, another Philadelphia resident, William Young, who emigrated from Scotland in 1784, as Margaret Hills documents, printed the first American Bible that contained the Metrical Psalms of David (Scots version). It is a school edition (Hills 25). Young also printed Bibles in 1791, 1792, and 1802 (some also with the Metrical Psalms).

In 1791, Isaiah Thomas (1749-1831), famous colonial printer, philanthropist, and patriot, published the first folio Bible in America (Hills 29) in Worcester and Boston, generally offered in two volumes, and offering customers up to fifty copperplate engravings. Thomas, a Quaker, had published A Curious Hieroglyphick Bible for children in 1788, with 500 small woodcuts . He published quarto, octavo, and duodecimo Bibles between 1791 and 1800, including the United States of Columbia Bible of 1797 (Hills 57). Thomas was editor of the Massachusetts Spy newspaper, and founder of the American Antiquarian Society which is still active today. He wrote The History of Printing in America publishedin Worcester (1810), and pioneered the illustrated Bible in America. Isaiah Thomas' son published the first Greek New Testament (1800), and his son-in-law, Anson Whipple, the first New Hampshire Bible (Walpole, 1815).

In 1791 Isaac Collins, a Quaker from Trenton, printed the first Bible of New Jersey (Hills 31), a large quarto. Remarkably, he obtained the support not only of Quakers, but of Presbyterian, Episcopal, and Baptist bodies, in his state. Dr. John Witherspoon, signer of the Declaration of Independence, president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) and a leader of the Presbyterian Church, supervised the work and wrote the introduction. Collins' family members and others meticulously proofread this Bible, and were paid for any printing errors found. Because of its very accurate text, Collins’ Bible was a standard for later Bible printers. Both Isaiah Thomas and Isaac Collins were particularly careful to ensure the accuracy and purity of the text, by getting the best possible Bibles from England and by hiring ministers as proofreaders. Collins had previously printed New Testaments in 1779 (Hills 4), 1780, 1782, and 1788.

The first American edition of John Wesley's translation of the New Testament, Explanatory Notes upon the New Testament (Hills 35), was published in 1791 in three volumes, with voluminous textual notes, each volume printed by a different printer (J Crukshank (image), Charles/Carl Cist (image), and Pritchard & Hall (image)). The first London edition had been published in 1755. Wesley had made 12,000 changes from the King James Version. The Wesley translation has had numerous printings. Early American editions were printed in 1806 (2nd edition, 2 volumes.), in 1812 (3rd ed., 2 volumes.), and in 1818 (4th ed., one volume). The 1791 Wesley translation was the third English translation published in America, the King James (1777) and Carey's Douay-Rheims (1790) antedating the Wesley version.

The first Delaware New Testaments (Hills 9 and 15) were printed by James Adams in Wilmington (1781, 1787). Well-known printer Hugh Gaine published the first New Testaments (Hills 21 and 27) in New York (1789, 1790 (image)). Hodge and Campbell printed by subscription, the first New York Bible (1792), an edition of Scottish minister John Brown’s Self-Interpreting Bible (Hills 37) which was firstpublished in Edinburgh (1778). George Washington was the first subscriber. Americas first hot-press Bible (1798) was published in Philadelphia by John Thomson and Abraham Small (Hills 62). Both the New York and the hot-press Bibles were folios in two volumes.

Nineteenth Century Innovations

Charles Thomson (1729-1824) in 1808 completed the first English translation, anywhere in the world, of the ancient Septuagint (Hills 153). Thomson was an Irish-born Presbyterian. He had come to America in 1739, received a Master of Arts, tutored at the College of Pennsylvania, and served as Secretary of the American Congress from 1774 to 1789. Thomson spent the next twenty years on his translation work. The Septuagint was an early Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible done by Jewish scholars in Alexandria, Africa, about 250 years before Christ. Thomson’s English Septuagint (without Apocrypha) was printed in three volumes, with the New Testament a fourth volume, by Jane Aitken, daughter of Robert Aitken (image). She was the first female publisher of a Bible in America and, perhaps, the world. The Thomson Old Testament was reprinted by S. F. Pells of Hove, England, in two volumes, in 1904 (Herbert 2134), and again in 1907 (image), and the New Testament in 1929 (image), all in London, England. A 1954 edition by Falcon’s Wing Press in Colorado (Hills 2540) (image) added a portion of the book of Esther not included in the original Thomson Bible. In 1815 Thomson also had published A Synopsis of the FourEvangelists,(image)essentially a gospel harmony he produced from a revised version of his 1808 translation. It was printed for him in Philadelphia by William McCullogh.

In 1800, Isaiah Thomas Jr. of Worcester, Massachusetts, printed the first Greek Testament in America (Evans 36952) (image). The first diglot (bilingual) New Testament in America, a Greek-Latin Testament edited by John Watts, was printed in Philadelphia in 1806 by S. F. Bradford (image). America’s first Hebrew Bible (based on Van der Hoog’s 1705 Amsterdam edition) was printed by William Fry and published by Thomas Dobson, in Philadelphia in 1814. At Boston in 1810, the first French New Testament in America was published, a de Sacy version, based on the Latin Vulgate (image). The first Protestant French New Testaments were printed in Ostervald's version in 1811 (image) and 1824, also at Boston. The first complete Bible in French was published by the New York Bible Society in 1815. The first New Testament printed in Spanish anywhere in the Western hemisphere was in 1819, a small duodecimo by the American Bible Society, in an edition of 2500(image). It is today a very rare item. Only a few copies are in collections. The 1819 Spanish Testament was from the 1793 translation of Padre Scio de San Miguel printed in Madrid, based on the Latin Vulgate. More precisely, it was from Scio's 1797 second edition. In 1824 the American Bible Society published America's first Spanish Bible, also in the Scio version, with the Deuterocanonical books (Protestant Apocrypha) (image), which was not removed until the fifth edition. It was stereotyped by A. Chandler of New York. The American Bible Society printed both Protestant and Catholic New Testaments in Portuguese in 1839, the Protestant version being that of J. Ferreira A. D'Almeida done in Batavia (modern day Indonesia), and the Catholic version being that of Antonio Pereira de Figueiredo from the Latin Vulgate (image). Hawaiian-language Gospels of Matthew (Rochester, NY, 1828), New Testaments (Honolulu, 1835), and Bibles (Honolulu, 1839) were published by the American Bible Society.

Mathew Carey and other commercial publishers could only compete with the non-profit Bible societies by going to more expensive, illustrated Bibles. In December 1808, the first of the Bible societies in America was organized, the Bible Society of Philadelphia. By 1809 Bible societies had been organized in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Maine. By 1816 there were more than 100 independent Bible societies in America. The first stereotyped Bibles in America (Hills 213) were from plates imported from England. William Fry of Philadelphia printed an initial run of 1050 Bibles and 750 New Testaments for the Bible Society of Philadelphia in the Fall of 1812 (image). The United States and England were at war, but both countries cooperated in this Bible effort. Stereotype printing greatly increased the availability of Bibles in America over the next decades. In 1815 the first American Stereotype Bible (first from stereotype plates made in the United States) was stereotyped and printed by D. & G. Bruce of New York (image). The first American stereotype Douay-Rheims Bible was published in 1824 by Eugene Cummiskey, Philadelphia, having been stereotyped by J. Howe of New York (image). The first folio Catholic Bible of America was published in 1825 in two volumes by Eugene Cummiskey (Hills 518), the Douay-Rheims from Rev. George Leo Haydock's folio Bible of 1811-14, Manchester, England. O'Callaghan elaborates: “It was published originally in 120 weekly numbers of 16 pages each, at twenty-five cents a number.” He continues “The price of the work bound, was $35, and the edition consisted of one thousand copies.” Some issues did not contain engravings or the date. It was not stereotyped.

The American Bible Society, established in 1816 in New York from many independent Bible societies, was by the Civil War publishing, without sectarian comment, over a million Bibles a year. Its first Bible was stereotyped in 1816 by E & J White of New York (Hills 303) and printed in an edition of 10,000 copies. Just two years later, in 1818, the American Bible Society had published missionary translations, John's Gospel in Mohawk and the Epistles of John in the Delaware language. Kentucky's first Bible (Hills 376) was published in Lexington by William G. Hunt in 1819, stereotyped for the American Bible Society from plates of D. & G. Bruce of New York. The stereotype plates were sent to the Kentucky Auxiliary Bible Society, which had 2,000 copies printed for use west of the Alleghenies. The New York Society in modern times became the International Bible Society (publisher of the New International Version), and the International Society in turn became Biblica. Baptists, dissatisfied with the American Bible Society's transliteration of the Greek word “baptize” in missionary translations, established the American and Foreign Bible Society (1836) and the American Bible Union (1850), the latter of which produced an immersionist version of the New Testament, The Common English Version,published between 1862 and 1864 (Hills 1764, 1773, and 1787 (image)). A second revision (Hills 1791) was reprinted a number of times up until 1874 (image). The work of these two organizations was taken over by the American Baptist Publication Society in the late nineteenth century.

Alexander Campbell (1786-1866) was born in Ireland and educated in Scotland. He became a Presbyterian minister, then a Baptist, before becoming a leader of the Restoration movement. He founded, with Thomas Campbell (his father), Barton Stone, and Walter Scott, what became known as the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). He produced, in the vernacular, a popular New Testament, The Sacred Writings (TheLiving Oracles) which, with some changes, is still in print today. The 1826 first edition (Hills 567), the first New Testament printed in Virginia, was published in Buffaloe (later Bethany), Brooke County in what is now the panhandle of West Virginia, above Wheeling. Early editions (1828 revised edition (image), 1832 revised and enlarged edition, 1833 stereotyped pocket edition, 1835 edition with few changes) were printed in Bethany, where Campbell lived and later founded Bethany College (1840). The Alexander Campbell New Testament was primarily a revision of a New Testament previously published in 1818 in London from eighteenth-century translations of Dr. George Campbell of Aberdeen, Dr. James Macknight of Edinburgh, and Dr. Philip Doddridge of London. Alexander Campbell also utilized Charles Thomson’s translation from the Septuagint. Campbell’s preface of about 100 pages gave the reasons for the revision. The 1826 New Testament turned the 1818 London version into one emphasizing immersion as the mode of baptism. The Campbell version was also the forerunner of the many modern-speech New Testaments of the twentieth century. Campbell, an astute student of Greek, based his text on the 1809-1810 edition of Griesbach’s New Testament. Marion Simms praised it as “unquestionably the best New Testament in use at the time” but Geddes MacGregor cautions that it is “marred by the unnatural English he inherited” and that the language “is heavy and dated.” Campbell's translation of The Acts of the Apostles, published by the immersionist-oriented American Bible Union in 1858 (image), a different version of Acts than the one in TheLiving Oracles. Campbell's mansion in Bethany is now a National Historic Landmark, and he is buried nearby.

The first Ohio Bible (Hills 702), a stereotyped Bible with Apocrypha and supplementary material, was printed in 1830 in Cincinnati by Morgan & Sanxay, who Hills refers to as “the largest printers in the western Country.” The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County has a copy. An earlier stereotyped 1828 Zanesville New Testament published by William Davis (image), which is not in O'Callaghan or Hills, but is listed in the Morgan Library of OhioImprints, 1796-1850, may be the first Ohio New Testament. The American Antiquarian Society in Massachusetts owns a copy which was formerly owned by Richard P. Morgan.

Noah Webster (1758-1843), became famous for his dictionary (1828) and The AmericanSpelling Book (“Blue-Back Speller”). His revision of the King James Bible, The Common Version (1833), was published by Durrie & Peck in New Haven, Connecticut (Hills 826) (image). Webster, a Congregationalist, updated antiquated English vocabulary, grammar, and punctuation. About 150 words and phrases from the King James Version were changed. He unfortunately, as Margaret Hills notes, substituted “euphemisms” for words he considered “very offensive to delicacy.” O’Callaghan noted that the text is from the quarto edition of the 1791 Isaac Collins Bible from which the publishing error in 1 Timothy 4:16 is repeated. The octavo Webster Bible was not a financial success, the King James Version being popular and entrenched.

Harper Brothers in New York issued, between 1843 and 1846, the most extravagant Bible produced in America (Hills 1161). Harper’s expenses amounted to over $20,000, a large amount for the mid-nineteenth century. The ponderous IlluminatedBible was embellished with 1,600 engravings by J. A. Adams, mostly from original drawings from the artist J. G. Chapman. The first electrotype in America from woodcuts had been produced by Adams in 1841, which enabled the making of this Bible. The Bible was reprinted in 1859 and 1866. (Hills 1692 and 1795).

James Murdock (1776-1856) translated the New Testament from the Syriac into idiomatic English (Hills 1477), a first for an American. Margaret Hills writes that it was “considered a faithful and scholarly translation” and was “well and widely received.” The translation was published by Stanford and Swords in New York in 1851, and reprinted at least six times in New York and Boston between 1852 and 1893. Murdock graduated from Yale, served as a Congregational minister, and was Professor of Ancient Languages at the University of Vermont, and of Sacred Rhetoric and Ecclesiastical History at Andover Theological Seminary. He was a noted linguist.

Isaac Leeser (1806-1868), originally from Prussia, was a leading Jewish Rabbi, and the foremost Jewish scholar of early America. In 1845-46 he edited, and published in five volumes, the Pentateuch in Hebrew and English, which he titled The Law of God (Hills 1273). It was printed by C. Sherman of Philadelphia. In 1849 Leeser published the Hebrew Bible, the first edition with points (vowels) that was printed in America. In 1853 he published The Twenty-four Books of the Holy Scriptures (Hills 1540), an English translation of the Hebrew Old Testament. Leeser spent 15 years in preparation for this acclaimed work. He researched mainly the works of German Jewish scholars, the only English work writer acknowledged being William Greenfield, the editor of Bagster’s Comprehensive Bible, a King James Version. Rev. Charles Hodge, a leading Presbyterian theologian at Princeton Seminary, praises Leeser's Hebrew Bible in the Princeton Review.

Leeser’s Philadelphia contemporary was Irish-born Francis P. Kenrick (1793-1863), who produced the first Catholic translation of the Bible in America. Kenrick presided over St Joseph's College (Bardstown, Kentucky), became a bishop (1830), founded a Philadelphia seminary, and became Archbishop of Baltimore (1851). His independent translation of the Bible, from the Latin Vulgate with judicious reference to the Greek and Hebrew, was published in six separate volumes from 1849 to 1862. The four Gospels came out in 1849 (Hills 1414) (image), the rest of the New Testament in 1851 (Hills 1484) (image), and a complete one-volume New Testament in 1862 (Hills 1761) (image). He published the Old Testament in four sections: The Psalms, Books of Wisdom, and Canticle of Canticles in 1857 (Hills 1665) (image); The Book of Job and the Prophets in 1859 (Hills 1708) (image); The Pentateuch in 1860 (Hills 1729) (image); and The Historical Books in 1860 (Hills 1730) (image). The New Testament was published in 1862, slightly revised from the versions of the 1849 and 1851 New Testament portions. Kenrick was not able to publish the whole Bible in one volume before he died, and his version, though widely acclaimed, never became the official American Catholic Bible. It should be noted that more than sixty editions of the Douay Bible were printed in nineteenth-century America, not including shorter portions of Scripture. The specific Douay Bible editions used by early American Catholics were, in general, those of Troy, Challoner, and Kenrick.

The American Bible Society published bilingual New Testaments, with the Scripture text in parallel columns, in order to meet the needs of America’s immigrant tide. These diglots included German/English (1849), Dutch/English (1849) (image), Danish/English (1849) (image), Swedish/English (1850), Spanish/English (1850), French/English (1853), Welsh/English (1855) and Portuguese/English (1857) (image). Some diglots, particularly the German/English, went through many editions. The Hawaiian/English Testament was published in New York by the American Bible Society (1857) (image). The Bible Society also published individual Gospel portions for missionary purposes, for example, John's Gospel in Mohawk (1818) and Mpongwe (1852).

By the beginning of the Civil War, the Bible, in whole or part, had been printed in the United States in more than thirty languages and dialects. The Bible or New Testament had been published in Natick/Massachuset/Algonquian (1661), German (1743), English (1777), Greek (1800), Latin (1806), French (1810), Hebrew (1814), Spanish (1819), Ojibwa/Chippewa (1833) (image), modern Greek (1833), Hawaiian (1835), Portuguese (1839), Choctaw (1848), Danish/Norwegian (1848), Dutch (1849) Swedish (1850), Italian (1854 - see O'Callaghan p. 338, no. 3), Welsh (1855), and Cherokee (1858). Individual books of the Bible were printed in nine additional American Indian languages: Mohawk (1818), Delaware (1818), Seneca (1829), Muskogee (1835), Shawnee (1836), Dakota (1839), Ottawa (1841), Potawatomi (or Pottawatomie) (1844), and Nez Perce (1845). Additionally, the Book of Acts was published in Arawak (Arrawack) by the American Bible Society in 1850 for indigenous people in South America. Selections of Scripture, but not a complete book of the Bible, were printed in Osage (1834), Oneida (1837), and Oto (1837). Luke’s Gospel was printed in Grebo (1848), and John’s Gospel in Mpongwe (1852), both for West Africans. An edition of the Gospels in Anglo-Saxon was published in New York by Wiley & Putnam (1846).

America, in its first two hundred years of Bible publication, had changed religiously, ethnically, culturally, and technologically. The work of publishing God’s Word had grown and diversified to meet the challenge.

Deserved Recognition

American Bible publication in the first two hundred years (1660 to 1860) has been surveyed. The significance of the early American Bibles is becoming more widely recognized. Of the American Bibles, the Eliot, Saur, Aitken, and Thomson Bibles, in particular, are being highlighted in traveling exhibits (known as “Passages”) around the United States from the Green collection. The exhibits also feature ancient manuscripts and historical Bibles from around the world. The collection has been assembled by Hobby Lobby’s President Steve Green. The Green Collection, containing more than 40,000 biblical antiquities, is among the world’s largest private collections, and will be permanently housed in a museum in Washington, D.C.

Ron Davis, an Indiana physician, collects early American Bibles and Bibles in many languages. Dr. Davis and his wife took courses at Westminster Seminary-West and served in Indonesia and Guyana. A Seventh Day Baptist, he traces his ancestry to seventeenth-century Particular Baptists in Rhode Island.

Selected Bibliography

Alderfer, E. G. The Ephrata Commune: An Early American Counterculture. Pittsburgh, PA, 1985.

Amory, Hugh. First Impressions: Printing in Cambridge, 1639-1989. Cambridge, MA, 1989.

Blumenthal, Joseph. The Printed Book in America. Hanover, NH, 1989.

Bradley, John. Ephrata Cloister: Pennsylvania Trail of History Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA, 2000

Bradsher, E. L. Mathew Carey, Editor, Publisher, and Author. New York, NY, 1966 [1912].

Brake, Donald. A Visual History of the English Bible. Grand Rapids, MI, 2008.

Brake, Donald. A Visual History of the King James Bible. Grand Rapids, MI, 2011.

Brumbaugh, Martin. A History of the German Baptist Brethren in Europe and America. Mount Morris, IL, 1899.

Carey, Mathew. Autobiographical Sketches, 1829. Reprint, New York, NY, 1970.

Clarkin, William, Mathew Carey: A Bibliography of His Publications, 1725-1825. New York, NY, 1984.

Cotton, Henry. Editions of the Bible or Parts thereof in English. Oxford, England, 2nd ed., enlarged, 1852.

Darlow, T. H. and H. F. Moule. Historical Catalogue of the Printed Editions of the Holy Scripture in theLibrary of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 4 volumes, London & New York, 1903-1911.

Dearden, Robert R. Jr., and Douglas S. Watson. An Original Leaf from theBible in the Revolution and an Essay Concerning It. San Francisco, CA, 1930.

Doll, Eugene E. Ephrata Cloister: An Introduction. Ephrata, PA, 1972.

Doll, Eugene E., and Anneliese M. Funke. The Ephrata Cloisters: An Annotated Bibliography. Philadelphia, PA, 1944.

Dore, J. R. Old Bibles. London, England, 2nd edition, 1888.

Durnbaugh, Donald F., ed. The Brethren in Colonial America: A Source Book. Elgin, IL, 1967.

Dwight, Henry, The Centennial History of the American Bible Society. New York, NY, 1916.

Eames, Wilberforce. Bibliographic Notes on Eliot’s Indian Bible, and His other Translations and Works in theIndian Language of Massachusetts. Washington, D.C., 1890.

Eames, Wilberforce. John Eliot and the Indians, 1652-1657. New York, NY, 1915.

Eames, Wilberforce. The Discovery of a Lost Cambridge Imprint: John Eliot's Genesis, 1655. Boston, MA, 1937.

Eason, Charles. The Genevan Bible: Notes on Its Production and Distribution, Dublin, Ireland, 1937

Eliot, John. The Indian Grammar Begun; or, An Essay to Bring the Indian Language into Rules. Cambridge, MA, 1666. Reprinted, Bedford, MA, 2001.

Evans, Charles. American Bibliography, 1639-1800, 14 volumes, 1903-1959. Volume 13 edited by C. K. Shipton. Volume 14 Index.

Flory, J. S. The Literary Activity of the German Baptist Brethren in the Eighteenth Century. Elgin, IL, 1908.

Frerichs, Ernest S., ed. The Bible and Bible in America. Atlanta, GA, 1988.

Green, James N. Mathew Carey: Publisher and Patriot. Philadelphia, PA, 1985.

Greenslade, S. L., ed. The Cambridge History of the Bible: The West from the Reformation to the PresentDay, volume 3. Cambridge, England, 1963.

Gutjahr, Paul. An American Bible: A History of the Good Book in the United States, 1777-1980. Stanford, CA, 1999.

Hall, Basil. The Genevan Version of the English Bible. London, England 1957.

Hall, Isaac H. American Greek Testaments. Philadelphia, PA, 1883.

Hatch, Nathan, and Mark Noll, eds. The Bible in America: Essays in Cultural History. New York, NY, 1982.

Herbert, A. S. Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of the English Bible 1525-1961. London, England, 1968.

Hills, Margaret T., ed. The English Bible in America: A Bibliography of Editions of the Bible & NewTestament Published in America 1777-1957. New York, NY, 1961.

Hixon, Richard F. Isaac Collins: A Quaker Printer in the 18th Century. New Brunswick, NJ, 1968.

Hocker, Edward. Germantown, 1683-1933. Germantown, Philadelphia, PA, 1933.

Hocker, Edward. The Sower Printing House of Colonial Times. Norristown, PA, 1948.

Jacobus, Melancthon Williams, ed. Roman Catholic and Protestant Bibles Compared. New York, NY, 1905.

Jenkins, Charles Francis. A Guidebook to Historic Germantown. Germantown, PA, 1902, 4th edition 1926.

Klein, Walter Conrad. Johann Conrad Beissel, Mystic and Martinet. Philadelphia, PA, 1942.

Kratzmann, Paul E. The Story of the German Bible: A Contribution to the Quadricentennial of Luther’sTranslation. St. Louis, MO, 1934.

Lamech, Brother, and Brother Agrippa. Chronicon Ephratense: A History of the Community of Seventh DayBaptists at Ephrata. Ephrata, PA, 1786. Translated by Max Hark, Lancaster, PA, 1899.

Lorenz, Alfred L. Hugh Gaine: A Colonial Printer-Editor’s Odyssey to Loyalism. Carbondale, IL, 1972.

MacGregor, Geddis. A Literary History of the Bible. Nashville, TN, 1968.

Margolis, Max. The Story of Bible Translations. Philadelphia, PA, 1943.

Mather, Cotton. India Christiana: A discourse, Delivered unto the Commissioners, for the Propagation of the Gospel among the Indians. Boston, MA, 1721.

Mather, Cotton. The Life and Death of the Renowned John Eliot,who was the first preacher of the Gospel tothe Indians in America. London, 1659. Reprint, London, England, 1820.

Mather, Cotton. “The Triumphs of the Reformed Religion in America.” Magnalia Christi Americana. 1708. Vol. 1. New York, NY, 1967. Pages 526-583.

Mayhew, Experience. Indian Converts: A Cultured Edition. 1727. Edited by Laura Arnold Leibman. Amherst, MA, 2008.

McGrath, Alister E. In The Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, aLanguage, and a Culture. New York, NY, 2001.

Moffett Thomas. The Bible in the Life of the Indians of the United States. New York, NY, 1916.

Morrison, Stanley. The Geneva Bible. London, England, 1935.

Norlie, Olaf. The Translated Bible, 1534-1934. Philadelphia, PA, 1934.

Nolan, Hugh J. The Most Reverend Francis Patrick Kenrick, Third Bishop of Philadelphia, 1830-1851. Washington, D.C., 1948.

Noll, Mark. A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada, Grand Rapids, MI, 1992.

Noll, Mark, et al., editors, Eerdmans' Handbook of Christianity in America. Grand Rapids, MI, 1983.

North, Eric, ed. The Book of a Thousand Tongues. New York, NY, 1938.

O’Callaghan, Edmund B. A List of the Holy Scriptures and Parts Thereof Printed in America Previous to1860. Albany, NY, 1861. Reprint, Detroit, MI, 1966.

One Hundred Years of Printing, 1785-1885. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, PA, 1935.

Orlinsky, Harry M., and Robert G. Bratcher. A History of Bible Translation and the American Contribution. Atlanta, GA, 1978.

Pennypacker, Samuel W. Historical and Biographical Sketches. Philadelphia, PA, 1883.

Pennypacker, Samuel W. The Settlement of Germantown, Pennsylvania, and the Beginnings of GermanEmigration to North America. Philadelphia, PA, 1899. Reprint, New York, NY, 1970.

Pope, Hugh, English Versions of the Bible. Revised & Amplified by Sebastion Bullaugh. St. Louis, MO, 1952.

Pope, Hugh. The Catholic Church and the Bible. New York, NY, 1928.

Powell, J. M. The Cause We Plead: A Story of the Reformation Movement. Nashville, TN, 1987.

Price, Ira Maurice. The Ancestry of Our English Bible, Philadelphia, PA, 1907.

Reu, Johann, Luther’s German Bible. Columbus, OH, 1934.

Reumann, John. Four Centuries of the English Bible. Philadelphia, PA, 1961.

Robinson, H. Wheeler, ed. The Bible in Its Ancient and English Versions. London, England, 1940.

Rumball-Petre, Edwin. America’s First Bibles: With A Census Of 555 Extant Bibles. Portland, ME, 1940.

Rumball-Petre, Edwin. Rare Bibles. New York, NY, 1963.

Sachse, Julius, The German Sectarians of Pennsylvania, 2 vols. Philadelphia, PA, 1899-1900. Reprint, 1971.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. A Bibliographical Catalogue of Books, Translations of the Scriptures, and OtherPublications in the Indian Tongues of the United States: With Brief Critical Notes. Washington, D.C., 1849.

Scudder, Horace E. Noah Webster. Boston, MA, 1897.

Seidensticker, Oswald. The First Century of German Printing in America, 1728-1830. Philadelphia, PA, 1893. Reprint, New York, NY, 1966.

Seventh Day Baptists in Europe and America, volume 2. Plainfield, NJ, 1910. Reprint New York, NY, 1980.

Shaw, Ralph R. and Shoemaker, Richard H. American Bibliography...1801-1805. 5 volumes. New York, NY, 1958.

Shea, John Gilmary. A Bibliographical Account of Catholic Bibles, Testaments...Printed in the United States. New York, NY, 1859.

Shipton, Clifford. Isaiah Thomas: Printer, Patriot, and Philanthropist 1749-1831. Rochester, NY, 1948.

Silver, Joel, ed. The Bible in the Lilly Library. Bloomington, IN, 1991.

Simms, P. Marion. The Bible in America. New York, NY, 1936.

Skeel, Emily E. A Bibliography of the Writings of Noah Webster. Edited by Edwin Carpenter, Jr. New York, NY, 1958.